Edit: Update – Jason Gorman weighs in with his thoughts in: Post-Agilism Explained.

What is Post-Agilism?

This requires a two part answer. Post-Agilism is:

- a growing movement of former Agilists who have moved beyond Agile methods, using a wide variety of software development tools and methodologies in their work.

- an emerging era. Now that the Agile movement has moved to the mainstream, what’s next?

Why Another Term?

I didn’t know of any other way to describe people who went through the Agile movement, and after a while decided they didn’t identify with being “Agile” anymore. They weren’t reversing back to big-up-front design, heavyweight processes, and were building on what they found effective in Agile methods.

“Post-Agilism” is a term I use that helps my thinking with this phenomenon. Some of the behavior is a reaction to dogmatic zealotry, like philosophical skepticism. For some reason, the term “religion” comes up an awful lot when “Agilism” is discussed, as described by Ravi Mohan, and Aaron West.

I’ve also seen behavior towards processes that is like scientific skepticism, or what might be better described as falliblism, that seeks to question process claims through investigation and scrutiny. That’s the “process skepticism” side. “Does this process ‘X’, as one of many tools we can use help us reach our goals of satisfying and impressing the customer? If not, why? What can we try that might work better?” I originally blogged the neologism “post-Agilism” in the hopes that it would help spur people to try out new ideas, and encourage those who were tired of Agile methods and wanted to build on them and move forward.

Jason Gorman and I both independently thought of the term “post-Agilism” because we were afraid that the industry would stop innovating. We both felt stuck in the “Agile” rut, and knew others who had worked through the Agile movement, and then said: “That was fun. Some things worked well, others not so well. What’s next?” This is sometimes the curse of the early adopter. What do you do after “Agile”, particularly when you feel that the innovation that the Agile movement injected into the software development world has slowed down, or maybe even stopped?

Gorman and I both came to use the term by looking at modernism vs. post-modernism in areas like architecture and art. Agile to us felt like modernism in architecture and art. Progressive, but with rules around the values and frameworks of implementation. There was this other thing going on though, where the rules of Agile were broken, and people created hybrids, or mashups of processes. This sounded more like the freewheeling, anything goes values of post-modernism. Hence the term: “post-Agilism.”

Isn’t the term “post-Agile” an oxymoron, or a fallacy?

It is if you use the dictionary definition of “agile”, but Brian Marick explains the difference of meaning of “Agile” (capital-A) quite well here:

It really gripes me when people argue that their particular approach is “agile” because it matches the dictionary definition of the word, that being “characterized by quickness, lightness, and ease of movement; nimble.” While I like the word “agile” as a token naming what we do, I was there when it was coined. It was not meant to be an essential definition. It was explicitly conceived of as a marketing term: to be evocative, to be less dismissable than “lightweight” (the previous common term).

…That’s why I habitually capitalize the “agile” in Agile testing, etc. It doesn’t mean “nimble” any more than Bill Smith means “a metalworker with a hooked blade and a long handle.

Note: I consider Brian to be one of the good guys – he is not an Agile marketer, but someone who is highly skilled at what he does, and is dedicated to driving the craft of software development forward. He has had an enormous influence on my career – Brian encouraged my exploratory testing efforts on Agile teams in particular. If you haven’t read his work, you should check it out on www.testing.com and www.exampler.com. From what I understand, Brian is as against the hype and dogma as we are, if not more so.

Jason Gorman explains further:

Adapting to circumstances is an agile strategy that can significantly improve our chances of success. But post-Agilism – [Agile] with a capital ‘A’ – is not about strategies. It’s about hype and it’s about dogma, and how they can – and, let’s face it, actually have – put a choke-hold on genuine innovation within the Agile community over the last few years. This is not what the Agile pioneers envisaged, I suspect. …I remain staunchly post-Agile, and see no fallacy in remaining decidely agile to boot! Just because you don’t like Big Macs, it doesn’t mean you hate beef burgers…

Is Post-Agilism Anti-Agile?

No. In fact, it can help preserve good practices that were popularized by the Agile movement in the face of a backlash. It’s better to think of it in terms of “after Agile” rather than “against Agile”. As Jared Quinert says:

When I started referring to you and others as ‘post Agile’, I used it to mean that you were the people whose thinking had moved on, that you were thinking about software development after Agile, and were reacting to stagnation. Some were uncomfortable of acceptance of Agile as an unquestionable best practice, not a solution to specific problems, or a set of principles which may or may not help your unique project.

Some people have expressed fear of returning to waterfall or phased approaches. This is a fear I share, and post-Agilism is a potential way out of that seemingly binary choice between Agile methodologies and big design up front, heavyweight processes. There are more than just those two choices, and in companies that have been burned by bad Agile implementations, it is tempting for them to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Post Agilism is one of many ideas to help counter that. Take the good, move forward and improve, don’t go back to the processes that weren’t working before just because you’ve had problems.

This thought of “after-Agile” isn’t so much a threat to Agile practices as an assimilation of them, combined with other ideas. Jason Gorman:

Those of us who consider ourselves “Post-Agilists” have taken what worked and cross-bred it with the best bits of dozens of other approaches and disciplines, creating new variants that have the potential to be even more exciting, daring and shocking.

I’ve heard post-Agilism referred to as a “process mashup” by others.

Post-Agilists aren’t necessarily “anti-Agile”, in fact they tend to incorporate a lot of Agile practices on projects, as well as other practices they find useful. Jason Gorman:

The Agile movement has successfully challenged the existing order and shaken the software industry out of a potential rut, bogged down by outmoded 19th century industrial thinking and “big process” dogma. It has opened the door to a very wide range of possibilities, and is now the catalyst for a Cambrian explosion of new ideas on how to deliver software and systems with bizarre, exotic-sounding names like Pliant Programming and Nonlinear Management.

Is Post-Agilism Superior to Agilism?

No – this isn’t about value judgments or superiority. Post-Agilism is a descriptor of something that we have seen and experienced. I’m personally not saying one thing is better than the other. I’m just saying people have moved on from Agilism for whatever reason. Who knows what the future will bring, and what will be remembered as being successful or “good” or “bad”. I’m ambivalent about it, but it is not a movement I started, people were displaying this kind of behavior long before I identified with it. I don’t think everything post-modernism brought us was necessarily good, but I like the fact that it added more ideas to the mix. Jared Quinert expresses ambivalence about the term: Maybe we are in “late agilism”. … “It’s bound to be renamed by someone else one day anyway.” We can be as wrong about any topic as anyone else.

Isn’t This Really Just “Pure Agile”? Aren’t You Just Reacting to Agile Corruption?

No, we are reacting and adapting to experience on our own projects, and to change. Furthermore, post-agile thinkers I’ve spoken to tend to be contextualists who, like the Context Driven Testing community, believe the value of a practice depends on its context.

Ravi Mohan:

…each agile practice (or the whole lot together with an appropriate label) makes sense only in certain contexts (certain types of enterprise software, with certain types of teams) even in the “uncorrupted”, “pure” state. A “pure agile” process is not superior to a “non agile” process de facto. Agile is not the “best way we know how to create software”. It is one way we know how to create software. It has no intrinsic superiority (except against obvious straw men like “pure waterfall” for projects with rapidly changing requirements). “Post Agile” is just an adjective that describes people who have used agile extensively, adopted what made sense, rejected the parts that didn’t work (and the hype) and choose to think for themselves. It is not a reaction against the perceived corruption of an originally perfect process. (From comments on Vlad Levin’s blog.)

A popular misconception is that if you are using an iterative lifecycle with incremental delivery, focus on communication, customer involvement, value testing, and delivering great software, then you are, by definition “Agile.” The Agile movement did not create these practices, (nor do prominent Agilist founders claim to have invented them) and it does not have sole ownership of them. Many of us were doing these things on projects in the pre-Agile era. In my own experience, I was on teams that used iterative lifecycles with two week iterations in the late ’90s. We looked at Rapid Application Development and adopted some of those practices, and retained what worked. We also looked at RUP, and did the same thing, and a big influence at that time was the Open Source movement. If you go back to the ’60s, thirty-forty years before the Agile Manifesto was created, Jerry Weinberg describes something very similar to extreme programming on the Mercury project. That doesn’t mean the Agile movement is wrong, it just shows that there are other schools of thought other than Agile when it comes to iterative, incremental development.

The Agile movement did not invent these practices – they’ve been around for a long time. Some of us were very excited about what the Agile movement brought to the industry, because we had also been working in that direction. What the Agile movement gave to us was a shared language, a set of tools and practices and advances in these techniques that can be very useful. The Agile movement has given us a lot of innovative ideas, but we can look at pre-Agile and Agile eras for great ideas and inspiration.

Another reason that some react negatively to the Agile movement as a whole is the “higher purpose” vibe that seems to emanate from Agilist gatherings. Michael Feathers put words to this, he described it as a “utopian undercurrent”, which is a brilliant and appropriate use of languge in this case. On the Agile Forums, Micheal Feathers said this on a thread:

… I think that there has been an undercurrent of utopianism in the agile community: “If only we get software development right, our businesses will succeed and the the death march will be relegated to the scrapheap of history.” As much as I’d like to believe that emotionally, I recognize that there is enough flux in an economy to make those sorts of states intermittent and somewhat unpredictable. There will be times when a team will be perfectly aligned with the surrounding organization, when the code will fly out of the finger tips and everyone will be happy. But, in general, organizations often act badly under stress. Projects can fail for reasons totally unrelated to a team’s performance.

This is an important insight. Tim Beck responds to a thread series on the Agile Forums where Brian Marick says:

Whereas the number of people new to Agile who describe their project as “the best project I’ve ever worked on” seems to be declining, and we believe work should be joyful…

Tim says:

I could be my typical snide and sarcastic self and say something in mock shock and awe, but I’m going to resist this time and actually applaud this important recognition. Agile isn’t all it is cracked up to be. It doesn’t always produce successful projects. It doesn’t always produce happy programmers. It doesn’t always produce delighted customers. The sooner we realize this, the sooner we can move on, or in the case of the Agile Alliance, the sooner they can attempt to patch up the beast.

Tim and I both agree with Brian that work should be joyful, that you should be able to enjoy what you are doing. Tim’s point is that just because your team is Agile, it doesn’t mean that you are guaranteed to have joyful a work environment. In fact, some Agile projects are as political, soul-crushing and demoralizing as any other project. It can be annoying to deal with that utopian undercurrent, particularly when people refuse to deal with issues because “we’re Agile!” – preferring an ideal over reality. Brian’s point is an important one to look into. Why does it look like this has changed over time? What is the real problem?

Won’t This Cause Harm to Agile Methods?

The value of Agile methods can stand on their own. Post-Agilism is just a term to clarify why some people choose to use Agile methods, and move on. There are still a lot of people who are perfectly happy with Agile methods. We are just reminding people that there are alternatives.

I’ve found the term has helped drive out confusion over mainstream Agile views, and this other group of activities that were similar, but didn’t really fit. If others find the term confusing and use it as an excuse to not even try Agile methods, that is their choice. They would probably find a different excuse if this term wasn’t around. If they are serious about trying Agile methods, this term should merely tell them that they are already behind the curve, and should hurry up learning something new in the hopes of improving.

One thing I have noticed is that Agilists are now looking at defending some of their positions, and looking for evidence to back up claims. I think that’s great. A little healthy skepticism and introspection can make good things stronger, and weed out practices that aren’t so good. If the term “post Agilism” helps people improve their work by making it defensible, that’s a good thing. Some of the criticism and skepticism is helping Agile practitioners improve their own work.

I also have trouble making a value judgment on behavior and activity that is going on as time passes and people embrace Agile methods, adapt, and some move away from that school of thought. It’s a descriptor, not a call to arms. The market will reward and punish our ideas over time. New ideas and experimentation aren’t bad things to me – stifling innovation is. One of the gifts the Agile movement gave us was an escape from the rut software development had fallen into. One of the dangers is apathy and complacency if Agile methods are touted as “the best way to develop software.” If we are already the best, why improve?

Where is the Post-Agile Manifesto?

There is no manifesto. This is not an organized group – it is a phenomenon of people around the world who have some sort of Agile experience, and have independently moved on. We are now discovering that there are more people doing this. Most post-Agilists I’ve talked to still value the points in the Agile Manifesto – they see it as a good start, but not the final answer. Furthermore, the Agile Manifesto is a bit like world peace. It is difficult to disagree with, but many disagree on implementations. Post-Agilists seem to want to expand the idea space on what those kinds of implementations might be.

What’s The Formula? Can I Buy the Process?

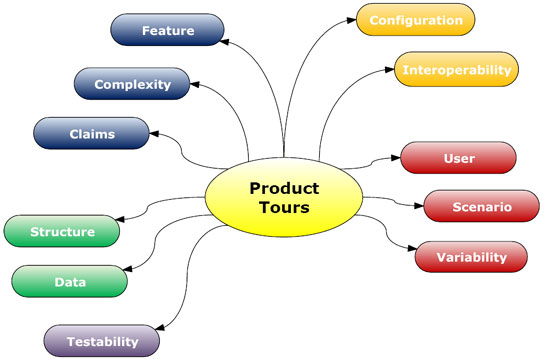

There is no formula. Software development is a complex business, with many factors. We’ve spent a lot of good effort in methodologies and tools, but there are many more variables to be aware of. Tools and processes are important, but it’s up to you to find out which ones work for you, in your context. I echo the Pragmatic Programmer’s advice for learning a new programming language every year, and Alistair Cockburn’s advice to try out and learn a new process frequently. Grow your toolbox. Focus on what goals the business is trying to achieve, and see how your technology, process and tool decisions help reach those goals – not the other way around.

Tim Beck has one way of putting this:

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again… I don’t know how you should build your software. No one but you can figure that out.

Isn’t Post Agilism Going to be Corrupted Too?

I hope the post-Agilism movement is a transitional movement that gets us back to worrying about good software development, instead of worrying about what pure “Agile”, “waterfall”, “RUP”,”CMM” et al “recommend” we do. Sometimes I’m not sure if post-Agilism is a movement as much as a phase. I started seeing post-Agilist behavior in about 2003, and it has grown organically without having founders, a manifesto or group of values to shepherd it. I’d rather characterize post-Agilism as a descriptor of something we see, rather than a goal we want to attain. If we see people who are fluent in Agile methods, but also draw from many other sources as they strive to develop the best software they can, we might say: “Look, there, that is post-Agilism in action.”

However, now that the cat is out of the bag, people will do whatever they want with the terminology. I’ve heard of Agilist marketers complaining that “Agile” is no longer a differentiator for them in the market. (Sometimes I wonder if there are there any software companies left that don’t call themselves “Agile”.) I imagine if the “Agile” branding devolution continues, someone is going to use “post-Agilism”, or some other term to fill the void in a similar way, along with other “new” ideas. The abuse will begin, the reactions will begin, and hopefully we just move beyond it, and forget about terminology and focus on building great software. It’s just the way of the world – people need to make money somehow, and time marches on.

What Does Post-Agilism Look Like?

Kathy Sierra was one of the first people to raise this issue. It’s a good one. My first answer was: “Let’s all find out together.” I still believe that, and while I have more experience and ideas now, I’m more interested in what you think. What are you, the reader doing or observing that looks like post-Agilism? What do you think it looks like and means? What creative combinations and cool amalgamations are you using as you experiment to improve your software development efforts?

James Bach has said this about post-Agilism:

It’s not a declaration of a new world order, it’s a transitional strategy on the part of and for the benefit of people who feel that Agile has lost its way.

Jason Gorman says: Post-Agilism is simply doing what works for you.

There are a lot of ways that people have moved on from Agilism and are doing something new. A common theme is to look at processes as a constantly evolving set of tools that need to be adapted to reach the goals of the software team and the business. This is often a fluid combination that extends beyond popular Agile definitions. For example, Alistair Cockburn was recently interviewed on “What’s Agile and What’s Not“. The answers are interesting. I particularly like his top ten list for figuring out whether your team is Agile or not. From a software development perspective it is fairly narrow, which makes it easier to decide whether you are Agile or not. Where it gets interesting, particularly when it comes to testing, is in point number 6. The “Agile Testing” view of testing is obsessed with automated testing, and it can be difficult to introduce other kinds of testing ideas in that community.

Back in the old days (for me circa 2001-2003) on Agile teams, if you were on an XP team, you could expect that kind of thinking on testing, but on other Agile projects, you had a lot more freedom to experiment to see what worked or not. That freedom to experiment as a tester on Agile teams is disappearing. Now what I see is an obsession with automating basic functional tests, that have to be “test-first”, which takes me back to the dark ages of testing where we pre-scripted all tests. That didn’t work so well, because we were only using confirmatory tests, and it forced testing to be predictive rather than adaptive. On Agile teams in the old days, I wasn’t so constrained, and it was nice to be able to have the freedom to be an investigative tester rather than just be a rubber stamp.

Nowadays, it seems testing ideas on most Agile teams I encounter are obsessed with automated unit testing, and are often forcing FIT way beyond its capabilities to meet some functional or acceptance test-first ideal, and the resulting maintenance issues that come along with it. (It’s not uncommon to see the top programmers spending all their time trying to get the FIT tests to work while the other programmers, business analysts and testers wait, sometimes for days on end for them to get their FIT infrastructure to work so they can write the code to satisfy the story.) One colleague of mine waited over a week for one report to be added to a system, 7.5 days were spent getting FIT to once again work with their system, and the other half day involved writing the story, and the actual program code. They remarked that this must be “test-dragging development”; at first, it was quite seamless and efficient, but as time went on, the maintenance costs of the automated tests were prohibitive.

There is some hope however, as exploratory testing seems to be gaining some currency in the Agile community. Most of the time though it feels like the Agile Testing ideals of “test-first” and “100% automation” win out, even if you have to force testing into a narrow definition to do it. That’s fine if that’s what you want to do in testing, but for some of us, that isn’t the be all and end all for testing. We see those ideals as part of a possible testing strategy. There are other examples other than testing where this stagnation, or narrowing of definitions of activities are taking hold in Agilism.

“Post-Agilism” is a term that gives permission to those who feel they are in the stranglehold of Agilism to move on and follow something that doesn’t seem to have currency in that community. It reminds them that there is more to software development than just the Agile movement.

Here are some other thoughts from around the web:

From the Software Underbelly blog: Post-Agilism:

Well, Halleluiah, I found some people talking about something other than following this ridiculous religion of Agilism. They saved me from one of my biggest rants. The original purpose of this column was to lambaste all the dogma drenched blather of Agilism. The loudest nails on the chalkboard for me was this attitude that process was EITHER predictive OR adaptive, i.e. my way or the highway.

…with Post-Agilism we take the good ideas but get back to looking at what works in a particular environment. I have always preached that good process is not from a book but an evolution. You design a process at the beginning as best you can and then continually adapt it as you go through releases. The process defined at the beginning is not nearly as important as how the evolution of that process proceeds from that moment forward.

Some people think that Lean is Post-Agile:

The Agile movement has given us some big advances, and also some big distractions. The good news is that we are perfectly free to toss out the distractions and substitute something better.

I’m personally not a big fan of Lean in software development, but he makes some interesting points.

This post “being agile in methodology” underlines what Post-Agilism can mean:

So, when are you using Scrum as methodology? In my project, we use lots of scrummish terms and tools, but for us being agile is also being agile in process. Why use the waterfall methodology when it comes to process? Why should we stick to tools we don’t find comfortable? We don’t. Our guideline is make it work for our team and our project. But when have we wandered so far of the beaten path that we no longer can call the methodology Scrum? Let’s wait ten years and see what it is called.It is good to know that we are not alone in this process, it actually has a name (though scorned by my team members) it is called post-agile…

In another example, Tim Beck decided to found the Pliant Alliance. Tim says:

Post-agilism to me is the more general description for what I did in founding the pliantalliance.org. I moved past Agile and started to think about what was good about it and what wasn’t. I started encouraging others to do the same. It turns out that I wasn’t the only one doing this and Jonathan came along and coined the term ‘post-agilism’ to describe what we all were doing.

What is Pre-Agilism? Isn’t that just waterfall?

Pre-Agilism is the period of time before the Agile movement was founded. This gets a little tricky though, because the Agile Manifesto signatories were also commentating on something they were witnessing and experiencing. Practices that were started prior to the “Agile” term creation were included under that umbrella. However, there are a lot of areas over the history of software development we can draw from.

Prior to the Agile movement, there were projects that used iterative lifecycles, were concerned with testing, customer involvement, and things of that nature. When I first read Martin Fowler’s The New Methodology, when I saw the first section “From Nothing, to Monumental, to Agile”, I interpreted that as describing the mainstream. There have long been projects and development ideas that rejected heavyweight, waterfall approaches, even when a phased “waterfall” approach was the dominant theory. I was on some of them in the late ’90s. We looked to the Open Source and Free Software communities as well as thinkers like Barry Boehm, Jerry Weinberg, Tom DeMarco, Tim Lister, Alan Cooper and others (including influential testing thinker James Bach) for ideas and inspiration.

That was an exciting time, and the Agile movement emerged as a dominating force in the iterative vs. waterfall debate. There were a lot of ideas that were experimented with and talked about in the fringes at that time. Some of the most influential for me were the usability and context-driven testing ideas. Going back further, there are classics on computer science that still have relevant lessons for us today.

There were also many who were using textbook waterfall phased approaches that were heavyweight. That was certainly a dominant thought in the late ’90s when I entered the game. The Agile movement was a breath of fresh air for people in those kinds of projects, and provided some great tools for dealing with this, particularly when it just wasn’t working. Here was an alternative that had a lot of credibility.

Why Aren’t You More Clear About This? Where Are the Examples?

I’ve held back a bit deliberately on my own ideas and examples because I wanted to see more ideas come to the fore. This is occurring slowly. I’ll add more on how I view software development and a post-Agile example or two in time.

What Do You Hope to Achieve?

With Post-Agilism, I just shared an idea I used to help reconcile something I was seeing happening, and experiencing myself. Others have found the term resonated with them, and they identified with what I was saying. Many have said they did find it encouraging. That continues to be a goal, to encourage those who want to improve software development in general, whether they are Agilists, post-agilists, or (insert fancy term here)-ists.

Others have reacted negatively to the term, and have started debating the value of it, as well as the value of the methods they believe in. I think that debate and communication of ideas is a wonderful thing. I hope we hear more about software development process and tool failures, not so much to say “I told you so!” or poke fun, but so that we all can learn.

This is what I mean by learning from mistakes. I have friends who are pilots. Any air accident is shared across the industry, and they openly share problems. In fact, they have to. One of my pilot friends told me that they are able to innovate because they focus on problems, and how to eliminate them and improve on them. One of my pilot friends said that this is part of the lifeblood of innovation in the aircraft industry. In software, we often downplay the problems, and vilify people who bring them to the forefront. We can learn a lot from our mistakes, and collectively move forward and innovate by looking at areas where we are weak. If this term helps spark some useful debate, collaboration and knowledge sharing to help us overcome areas we are weak in, I think that would be great.

At the end of the day, Post-Agilism is just an idea, or a model that some of us find helpful right now. Don’t find it helpful? Don’t worry about it. We aren’t trying to change minds, we’re just trying to get people to think about what they are doing. If Agilism works for you, great! If something else does, that’s great too. There are a lot of good ideas to choose from, particularly if you expand your view.

Maybe one day, we’ll just get back to calling all of this “software development” and we’ll pick and choose the right tools for the job to help us reach out goals. We don’t have to pick sides – there are great ideas to be found from all kinds of sources that we can learn from and try.